INTRODUTION

There are performances that entertain, and then there are performances that quietly redraw the map of music history. On January 14, 1973, when Elvis Presley stepped onto the stage in Honolulu for the globally televised concert known as Aloha from Hawaii via Satellite, he was not simply adding another show to his résumé. He was standing at a cultural crossroads. And when he launched into “Johnny B. Goode,” something remarkable happened. It became A rock ’n’ roll salute under Hawaiian lights where legacy, joy, and raw energy meet in one fearless performance.

To understand the weight of that moment, we have to step back. By 1973, Elvis was no newcomer trying to ignite radio waves. He had already changed the sound of American music, reshaped stage presence, and built a catalog that bridged gospel, country, rhythm and blues, and rock ’n’ roll. Yet instead of leaning exclusively on his own hits, he reached back to a foundational anthem written by Chuck Berry in 1958. “Johnny B. Goode” was already canon. It was a song etched into the DNA of rock history. For Elvis to perform it live before a global audience was not an accident. It was intention.

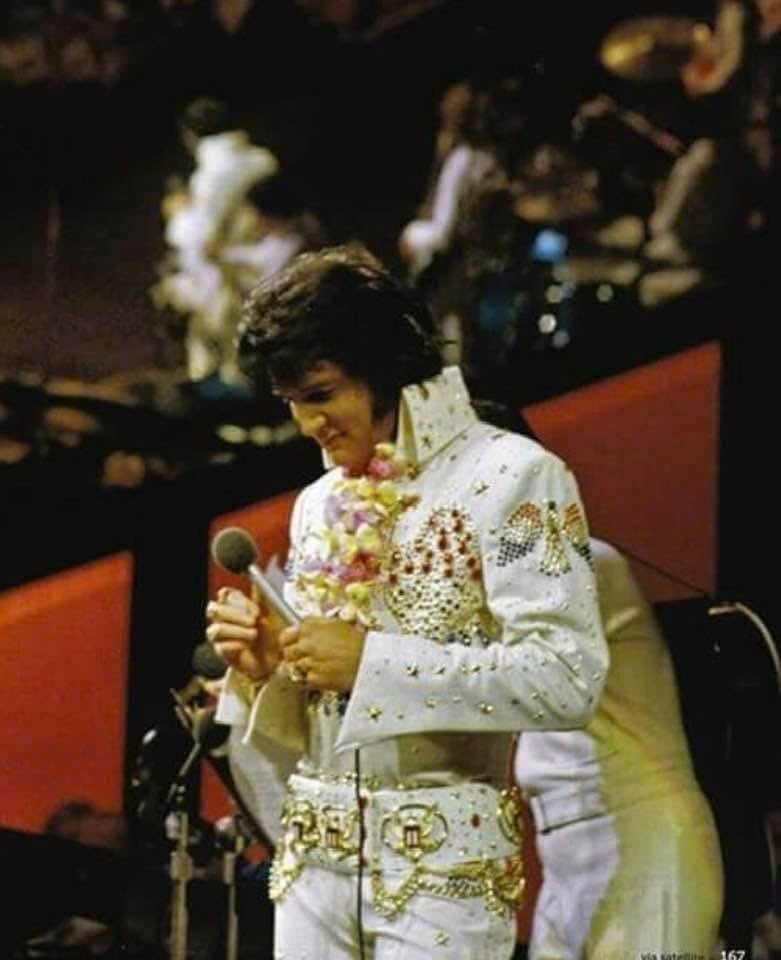

The broadcast itself was unprecedented. Aloha from Hawaii via Satellite became the first solo-artist concert transmitted live around the world via satellite, reportedly reaching over a billion viewers. In an era before streaming and instant replay, that kind of reach felt almost mythic. Families gathered around televisions. Time zones blurred. Honolulu became the center of the musical universe for a single evening. And Elvis, dressed in his now-famous American Eagle jumpsuit, was more than a singer on a stage. He was an ambassador of a distinctly American sound.

When the opening riff of “Johnny B. Goode” cuts through the Hawaiian air, Elvis does not rush. That restraint is crucial. There is a subtle smile in his phrasing, a sense that he understands the song’s place in history. He doesn’t treat it like a relic. He treats it like living fire. His voice here is looser than in his dramatic ballads, more relaxed than in his gospel showcases. He leans into the groove. He trusts the band. He allows space between lines, as if savoring the rhythm rather than chasing it.

Behind him stands a band capable of both precision and power. James Burton, whose guitar work had already earned respect across genres, drives the arrangement forward with clarity and bite. Burton doesn’t attempt to overshadow the song’s iconic riff. Instead, he converses with it. The tone is sharper, fuller, adapted for a grand stage without sacrificing its roots. The rhythm section locks in with confidence, giving the performance an almost conversational momentum. It feels alive rather than rehearsed.

The magic of this moment lies in balance. Elvis honors Berry’s blueprint without imitation. He recognizes the architecture of the original while stepping into it with his own lived experience. When he sings about a country boy who “could play the guitar just like ringing a bell,” the lyric takes on new resonance. Elvis, too, had been that young dreamer from modest beginnings. He had carried that spark into living rooms, theaters, and arenas around the world. In 1973, he was no longer chasing opportunity. He was embodying legacy.

There is another layer here that mature listeners often sense more deeply. By choosing “Johnny B. Goode,” Elvis quietly acknowledged the Black pioneers whose creativity shaped early rock ’n’ roll. In front of a global audience, he paid tribute not by lecture, but by performance. He did not dilute the song’s spirit. He amplified it. That act alone carries weight. It reflects an artist aware of the shoulders he stood upon.

What makes the Honolulu rendition unforgettable, however, is the unmistakable joy. Elvis appears energized, relaxed, even amused by the song’s youthful optimism. He interacts easily with the musicians. His movements are fluid, not forced. There is no frantic attempt to prove relevance. That chapter of his career had already been written. Instead, what we see is a seasoned performer reconnecting with the spark that first defined him. It is not nostalgia. It is continuity.

Throughout the Aloha set, Elvis delivered powerful ballads and stirring gospel numbers that showcased control and emotional gravity. Yet “Johnny B. Goode” cuts through that intensity like sunlight. It is playful without being careless. It is tight without being rigid. And in that contrast, it reminds the audience that rock ’n’ roll at its core is about motion, possibility, and release.

The broader context of the concert amplifies the impact. This was not a small club performance. This was a satellite broadcast reaching continents. The weight of expectation could have turned any song into spectacle. Instead, Elvis keeps the focus on groove. The horns punctuate with crisp confidence. The guitar lines flash but never overwhelm. The rhythm pulses steadily. And Elvis stands centered, not chasing the energy of the crowd, but directing it.

That composure matters. By 1973, Elvis had conquered radio charts, dominated film screens, and filled countless venues. He had nothing left to prove. Yet in choosing to spotlight a foundational rock anthem, he signaled something profound. He was reminding viewers where the fire began. He was honoring the lineage that carried him forward. And he was doing it with warmth rather than bravado.

The meaning of “Johnny B. Goode” has always revolved around possibility. A young musician rising through talent and determination. Music as escape. Sound as destiny. When Elvis sings it in Honolulu, the dream is no longer theoretical. It is lived. That gives the performance emotional gravity. He is not projecting ambition. He is reflecting on fulfillment.

Decades later, audiences continue to revisit this moment because it feels honest. There is no overproduction obscuring the groove. No attempt to modernize the song beyond recognition. Elvis steps inside the framework and allows it to breathe. The Hawaiian lights, the satellite cameras, the cheering crowd all become secondary to the rhythm that pulses through the song.

For longtime fans, this performance represents a bridge. It connects the rebellious spark of the 1950s with the global sophistication of the 1970s stage. It demonstrates that rock ’n’ roll can mature without losing vitality. It affirms that legacy does not require reinvention at every turn. Sometimes it simply requires respect.

When we watch Elvis perform “Johnny B. Goode” at Aloha from Hawaii via Satellite, we witness more than a cover. We witness conversation across generations. Chuck Berry laid the groundwork. Elvis carried it to a global audience. And through that exchange, rock ’n’ roll reaffirmed its durability.

There is a quiet lesson here for modern artists and listeners alike. Trends shift. Technologies evolve. Broadcast methods transform from satellite signals to digital streams. Yet the essence of a song grounded in authenticity remains untouched. In Honolulu, under those bright Hawaiian lights, Elvis proved that great music does not age out of relevance. It expands.

In the end, what lingers is not just the image of the white jumpsuit or the scale of the audience. It is the sound of a seasoned voice leaning into a timeless riff. It is the sight of a band locked into rhythm. It is the realization that legacy is not about standing above history, but standing within it.

And for a few electric minutes in January 1973, as televisions flickered across continents, Elvis Presley did exactly that. He revisited rock ’n’ roll’s foundation, lifted it into the present, and offered the world a reminder: the fire that began in small rooms and on humble stages can still burn bright on the largest platform imaginable.

That is why this performance endures. Not because it was loud. Not because it was extravagant. But because it was sincere. It was rooted. It was alive.

Under Hawaiian lights, rock ’n’ roll did not simply echo its past. It stood tall, smiled, and moved forward.