INTRODUCTION

There are songs that climb the charts. There are songs that win awards. And then there are songs that do something far more complicated — they divide a nation in real time.

“THE LYRIC THAT SPLIT AMERICA — AND THE QUESTION THAT SET FIRE TO THE DEBATE: ‘ISN’T HE CANADIAN?’”

That headline may sound dramatic, but in 2002, it did not feel exaggerated. It felt immediate. Urgent. Unavoidable.

To understand the firestorm that followed, you have to return to a country still reeling. In the months after September 11, 2001, America was not simply grieving. It was searching — for security, for identity, for clarity. Flags appeared in neighborhoods where they had never flown before. Church pews filled. Talk radio grew louder. Television anchors spoke more slowly, more carefully.

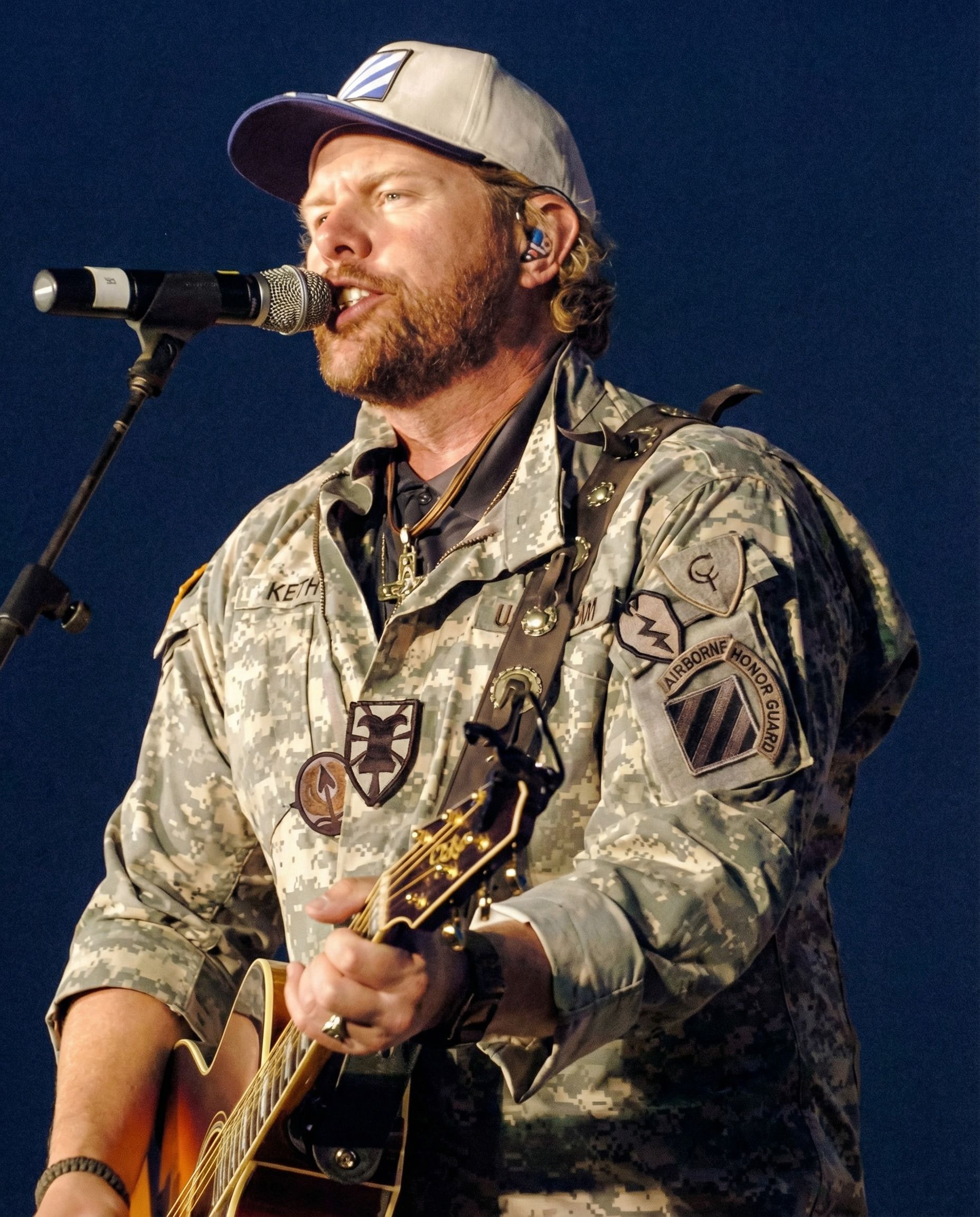

And in the middle of that emotional landscape, Toby Keith did not write a song meant to soothe.

He wrote one meant to confront.

When “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue (The Angry American)” arrived in 2002, it did not ask permission. It did not lean on metaphor or poetic restraint. It moved straight to the gut. The instrumentation was bold. The delivery was unapologetic. The tone was clear: this was not reflective mourning. This was response.

And then came the line that would echo far beyond country radio:

“We’ll put a boot in your… — it’s the American way.”

For millions of listeners, that lyric was not about aggression for its own sake. It was about release. It was about putting words to an anger many felt but did not know how to articulate publicly. In small towns and big cities alike, people sang along not because they loved confrontation, but because they recognized the emotion.

Country radio embraced it immediately. Crowds at live shows responded with thunderous approval. Veterans, first responders, and families who had watched the towers fall felt seen in a way that quieter ballads had not provided.

But not everyone heard the same song.

To critics, the lyric felt combustible. They worried it simplified patriotism into defiance. They questioned whether national grief should be expressed in such sharp terms. Some commentators suggested that art, especially in moments of trauma, carries responsibility beyond individual emotion.

And so, what might have been a typical chart-topping single became something else entirely: a cultural litmus test.

The debate spilled into living rooms, newspaper columns, and cable news panels. Was this patriotism? Was it provocation? Could it be both?

It is here that the conversation became even more layered — and stranger. As the song surged in popularity, an unrelated but persistent question surfaced in certain discussions: “Isn’t he Canadian?” The confusion stemmed from broader conversations about country music’s global reach and the nationality of other artists associated with patriotic anthems. The question itself was misplaced in Toby Keith’s case, yet its circulation revealed something deeper.

The debate was no longer just about a lyric. It was about ownership — who gets to define patriotism, who gets to sing it, and who gets to question it.

Then came July 4th.

Independence Day in America is not merely a holiday. It is performance. Fireworks, televised concerts, national stages that attempt — however briefly — to present unity in song. In 2002, one such national broadcast was being assembled. The intention was clear: celebration, remembrance, shared identity.

Toby Keith’s presence initially seemed natural. His song was everywhere. His name was part of the national conversation. Supporters assumed he would be featured prominently.

And then, quietly, he was not.

There was no dramatic press conference. No heated on-air announcement. Just a lineup that no longer included him. Officially, organizers suggested the tone of the event required something less intense. The phrasing was careful. Diplomatic.

Unofficially, the question grew louder.

Who gets to decide how patriotism should sound?

For many of Keith’s supporters, the removal felt like censorship. They argued that patriotism is not always gentle. That history itself contains moments of fierce resolve. That to remove the song from a national stage was to deny a real and widely felt emotional response.

For others, the decision felt measured. They believed Independence Day broadcasts should unify rather than polarize. That in a country of diverse beliefs and backgrounds, a publicly funded celebration should lean toward inclusion over confrontation.

What made the moment unforgettable was not simply the cancellation. It was how clearly it revealed a divide that had already been forming beneath the surface.

Two Americas, listening to the same line, hearing completely different meanings.

On one side were those who believed the lyric honored sacrifice and resolve. On the other were those who felt it risked hardening grief into something less reflective.

Country music has long walked this tightrope. It is, at its core, storytelling. It reflects its audience — their work, their faith, their pride, their frustration. In times of calm, that reflection feels comforting. In times of crisis, it can feel explosive.

Toby Keith did not retreat from the song. He continued to perform it. He defended it publicly, emphasizing that it was written in response to a national tragedy and in memory of his father, a veteran. He acknowledged the controversy but did not apologize for the emotion behind it.

Over time, the intensity of the public outrage softened. That is the nature of cultural storms. They blaze, they divide, and eventually they settle into memory. Yet the questions raised in 2002 did not disappear.

Was the song simply reflecting the mood of the moment? Or did it shape it? Did removing Keith from that July 4th stage protect unity, or did it amplify the very division it sought to avoid?

Years later, “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue” still carries weight. Not because everyone agrees with it — but because it forced a national conversation that went far beyond melody.

It challenged the assumption that patriotism must be polite. It questioned whether anger has a place in collective memory. It exposed how quickly cultural institutions move to manage tone in times of tension.

And perhaps most significantly, it demonstrated the power of country music as more than background soundtrack. In that moment, it became frontline dialogue.

For older listeners who lived through that period, the memory remains vivid. They remember where they were when they first heard the song. They remember the arguments at family gatherings. They remember watching television on July 4th and noticing the absence.

For younger audiences discovering the song now, the context may feel distant. But the underlying questions are not. Who decides what is appropriate? Who defines national identity? And when art provokes discomfort, is that failure — or function?

The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville stands as a reminder that country music has always told the complicated stories of America. It has celebrated unity and exposed fracture. It has comforted and confronted.

Toby Keith’s 2002 anthem sits firmly in that lineage.

It was not subtle. It was not universally embraced. But it was honest to the emotion that inspired it. And in times of upheaval, honesty often arrives louder than expected.

Looking back, it is tempting to simplify the episode into a tidy narrative: controversial lyric, canceled appearance, divided reaction. But real cultural moments resist simplicity. They ripple outward, influencing conversations for years.

The debate around that song was never just about a boot-in-your response. It was about voice. About space. About who gets the microphone during national reflection.

And that lingering backstage question — “Who gets to decide how patriotism should sound?” — still resonates.

Because it was never just about Toby Keith.

It was about a country arguing with itself, through song.

One controversial moment. One cancellation. Two Americas hearing the same melody in different keys.

And an argument that, in truth, never really ended.